How many of you remember the gopher from Winnie the Pooh?[1] He was not an original character in the book, but he appeared in the American Disney movie.[2] He would pop up with his speech impediment and speak with a funny ‘S’ sound. “Say…what’s wrong Sonny?’ Mr. Gopher’s S’s are Sibilants[3]—consonants made with the tip or front part of the tongue. His signature whistle of his ‘S’s was either endearing or annoying, depending on your point of view.[4] There’s an episode where Pooh mimics Gopher while asking for honey, and Gopher tells Pooh he should do something[5] about the speech impediment he himself has, before handing him the honey.[6] In Winnie the Pooh, Gopher is always quick to remind everyone: “I’m not in the book!” It’s lighthearted and endearing, but it also marks him as different. He doesn’t quite fit the same way as the others, although he’s still part of the story in his own way. In our text today, a difference in pronunciation became a matter of life and death. Something as small as a sound divided brothers and turned family into enemies. Before we get into our that, I want to lay a little of the framework for the tension that is underneath it all.

The twelve tribes come from the twelve sons of Jacob, and the seeds of rivalry were sown back in Genesis. Joseph was Jacob’s favored son. He was given the coat of many colors, was sold by his brothers, but later rose to power in Egypt and sired two sons. When Jacob blesses his sons near his death in Genesis 49, Judah receives the royal blessing: “The scepter will not depart from Judah.” and Jacob tells Joseph that his grandsons, Manassah and Ephraim, will also be like sons to him. In a reversal of the expected, Jacob crosses his hands and places his right hand (the stronger blessing) on the younger son, Ephraim, and his left on the older son, Manasseh. Jacob says, But his younger brother will be greater than he, and his descendants will become a group of nations. Genesis 48:19

Long after the judges, and the institution of the monarchy, the kingdom eventually split, and Ephraim dominated the Northern Kingdom, and Judah the Southern Kingdom. Prophets often use “Ephraim” as shorthand for the entire northern kingdom of Israel. But that is much later. Let’s go back with a quick overview of Ephraim—in the book of Judges. Joshua, who rises up to be a leader after Moses, was an Ephraimite. But after his death, there is no leader to replace him from the tribe of Ephraim.[7] Judah is the first tribe to go up in battle in Judges 1, showing early leadership. The Ephraimites are also quick to answer the call to battle[8], and Ehud, a Benjamite, is the one that leads them against Moab. Ephraim holds the central territory where the tabernacle rests at Shiloh , effectively making it the spiritual center of Israel for generations. Deborah judges in the hill country of Ephraim, but she calls Barak to go into war—a man from Naphtali, which leaves Ephraim out. Tola, our minor judge from last week, was acting as a judge—in the hills of Ephraim, but he was from the tribe of Issachar. As the book of Judges goes on, Ephraim has a sort of tribal arrogance. They complain when Gideon doesn’t call them early enough to the battle. Gideon manages to calm them down.

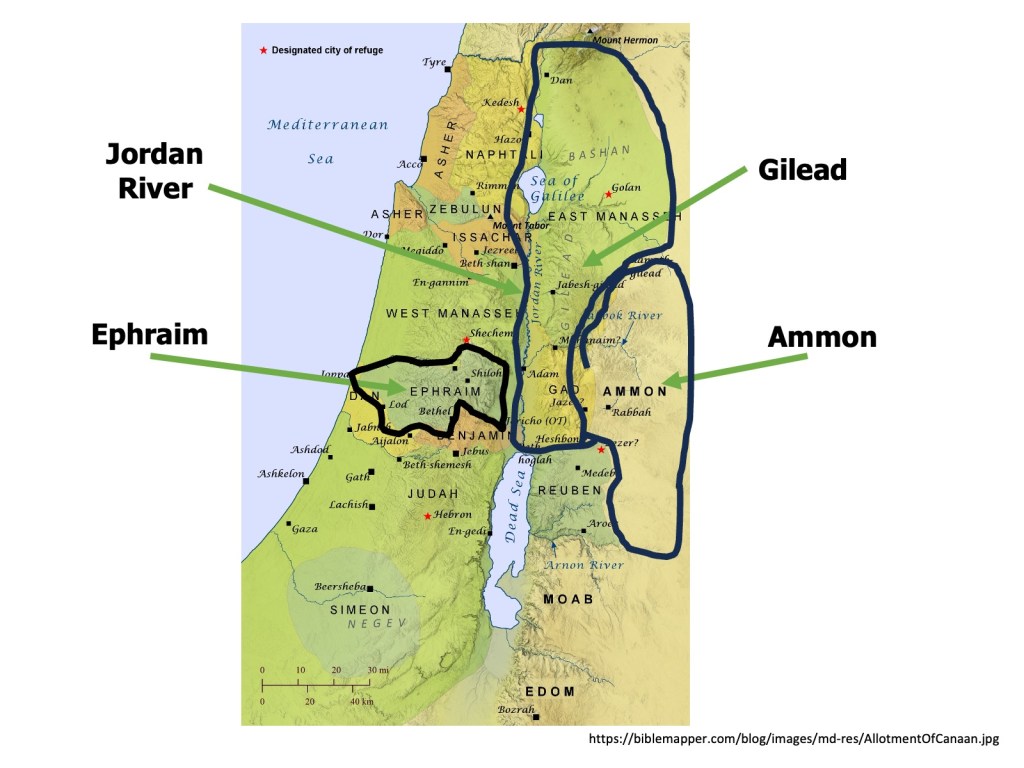

Our current judge, Jephthah, comes from Gilead, a large geographical area, which includes the tribe of Gad, Reuben and Manassah. This makes him part of the greater “House of Joseph,” making him a sort of cousin to the Ephraimites. But they occupy different sides of the Jordan River. Gilead is on the East side of the Jordan, Ephraim is on the west side. And there is a subtle tension between the two groups.

In our last chapter, Jephthah negotiated with the King of Ammon. He gives a long diplomatic speech, rich in historical and religious content. One of the reasons he may have been able to do so well is because Gilead had more in common with Ammon than with Ephraim.[9] He lives nearby. We know that the people of Israel were worshipping the gods of Ammon, along with the gods of the other surrounding nations.[10] It stands to reason that over generations, the people in the Gilead region probably also picked up some linguistic similarities — shared accents, loanwords, or speech rhythms. Jephthah may have had the ability to “speak both languages,” figuratively or perhaps even literally, which makes him a good bridge between the nations — and yet, ironically, that same linguistic versatility becomes a critical moment for division in the next chapter.

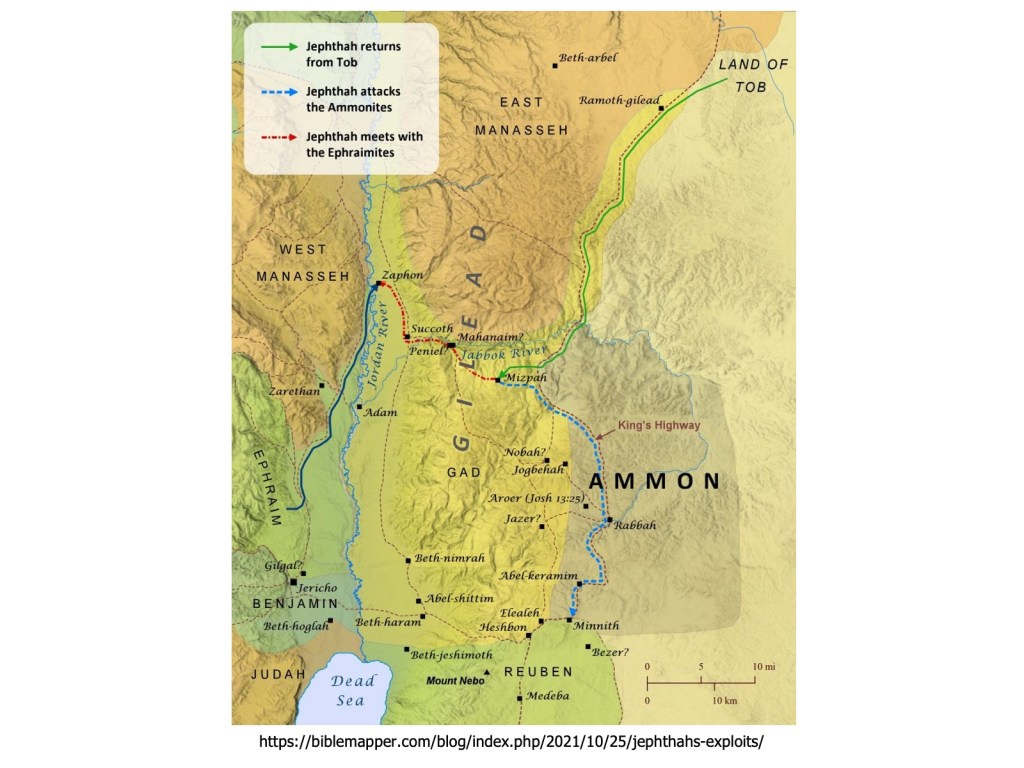

Jephthah may envision himself as a powerful negotiator—He was able to get the role of governor over the people of Gilead, he TRIES to persuade the king of Ammon that the territory does in fact belong legitimately to the Israelites—but he ends up going to war. He attempts to bargain with God to win the battle, but it ends tragically. Now he will need to practice his negotiating skills once more.[11]

The Ephraimite forces were called out, and they crossed over to Zaphon. They said to Jephthah, “Why did you go to fight the Ammonites without calling us to go with you? We’re going to burn down your house over your head.” Judges 12:1

Well, that escalated quickly! Once again the Ephraimites are feeling slighted. They’ve been left out of the battle, and Jephthah is a Gileadite, which to the Ephraimites is like living on the ‘wrong side of the tracks.’[12] It’s on the other side of the Jordan River, close to Ammon. The Ephraimites do not even wait for a reply before threatening to burn Jephthah’s house down. They seem eager to have an argument with their fellow Israelite. Jephthah is immune to their threats, however. He has already destroyed his own house—he has offered up his only daughter as a burnt offering.[13] Jephthah has been good with words before—in his case against the Ammonite king. But here, he seems to want to irritate the Ephraimites.[14]

2 Jephthah answered, “I and my people were engaged in a great struggle with the Ammonites, and although I called, you didn’t save me out of their hands. 3 When I saw that you wouldn’t help, I took my life in my hands and I crossed over to fight the Ammonites, and the Lord gave me the victory over them. Now why have you come up today to fight me?” Judges 12:2-3

It’s a good question. Where WERE the Ephraimites in battle? Instead of thanking Jephthah or congratulating him in the victory, they act a bit jealous, and their pride is wounded.[15] The same kind of thing happened in chapter 8 with Gideon, but Gideon placated the Ephraimites and responded gently[16], saying, ‘GOD has given the leaders of Midian, Oreb and Zeeb into YOUR hands. What was I able to do compared with you?’[17] Jephthah says, where were you when “I” needed you? “I” placed my life in MY hands, and “I” crossed over to fight, and the Lord gave ME the victory…[18]

4 Jephthah then called together the men of Gilead and fought against Ephraim. The Gileadites struck them down because the Ephraimites had said, “You Gileadites are fugitives[19] from Ephraim and Manasseh.” 5 The Gileadites captured the fords of the Jordan leading to Ephraim…Judges 12:4-5a

The Ephraimites call the Gileadites fugitives, which may be a sore spot for Jephthah from his early life. It’s a bit of a personal insult.[20] Just like the Ephraimites didn’t wait for Jephthah to answer, Jephthah does not wait for any kind of reconciliation before summoning the men of Gilead to fight.[21]

As they lose the battle, the Ephraimites have found themselves on the wrong side of the tracks[22], and they try to slip back across the Jordan river to safety. The Jordan river is a geographical and psychological barrier between eastern and western Israelites.[23] Now we have a tribal war. It’s hard to tell who your enemy is when you are fighting against people from your own country, so Jephthah’s men come up with a secret password.

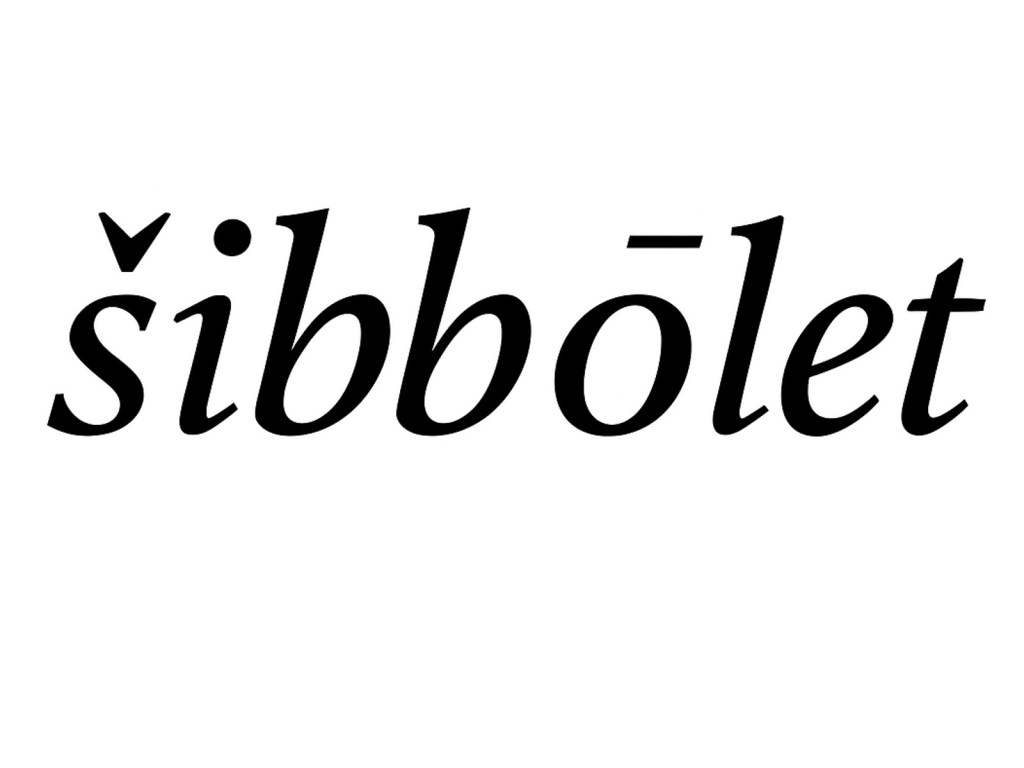

…and whenever a survivor of Ephraim said, “Let me cross over,” the men of Gilead asked him, “Are you an Ephraimite?” If he replied, “No,” 6 they said, “All right, say ‘Shibboleth.’” If he said, “Sibboleth,” because he could not pronounce the word correctly, they seized him and killed him at the fords of the Jordan. Forty-two thousand Ephraimites were killed at that time. Judges 12:5b-6

The word Shibboleth means something lifegiving—an ear of corn or a stream of water.[24] But it became a word of death. It became all about the pronunciation of the word. During a Frisian rebellion in the 1500’s there was a farmer and pirate known for his size, strength and bravery. Pier Gerlofs Donia would come upon ships and ask the crews to repeat this phrase: “Butter, rye bread and green cheese, whoever cannot say that is not a genuine Frisian.” Here’s how that sentence sounds in Frisian.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nl-Schibbolet-fries.oga[25]

Bûter, brea, en griene tsiis; wa’t dat net sizze kin, is gjin oprjochte Fries If the crew could not say this sentence correctly, their ships were plundered. Soldiers who could not say it were beheaded.[26] This kind of thing happened in World War 2, when English-speaking Allied personnel in Europe would use passwords with w-sounds, pronounced with a “v” by native speakers in German.[27] In the 1948 war, Israeli forces used passwords with p sounds which are not found in Arabic, and THEY would replace it with a b sound. Spanish speaking Argentinians had a hard time saying, “Hey Jimmie”, so, the Scots Guards in the Falklands War in 1982 used that as their password. In the tv show ‘The West Wing’ the president wanted to check to see if a Chinese man seeking refuge in America was actually a Christian and gave him a ‘Shibboleth’ test. It’s a pretty good example, if you want to watch it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fqkaBEWPH18

In this instance, the Gileadites would have a high vowel sound—[28] with the ‘I’ sounding like the “I” in machine.[29] The š[30] has a symbol over it, which indicates the ‘sh’ sound,[31] like SH-ibbolet. But Robert Woodhouse proposes that the sound was not conspicuous.[32] Maybe the tongue would be close to the roof of the mouth without touching. The Sh sound could have sounded more like an ‘S’. (Sheebolet) Can YOU say it? Ronald Hendel proposes that the Transjordanian pronunciation—those living on the East side of the Jordan— which would include Ammon and Gilead, their pronunciation…was heard by the Cisjordanian Hebrew speakers as their pronunciation of samek, another ‘S’ sound in the Hebrew. Only the Gileadites could detect the difference.[33] In the Hundred Acre Wood, Gopher’s difference was accepted with humor and affection. In Judges, Ephraim’s difference was punished with hostility and bloodshed. Jephthah turns the word into a weapon.[34] All of his life,

Jephthah chose a culture of conflict

Othniel—captured Arameans. Ehud—killed the king of Moab. Shamgar—killed some Philistines. Barak—defeated Canaanites, and Jael killed Sisera, their general. Gideon—defeated the Midianites and also destroyed two Israelite cities. Abimelech—killed his own half-brothers and destroyed Shechem. Jephthah—has offered up his daughter, and subdued the Ammonites, but now killed forty-two thousand fellow Israelites. He killed more Ephraimites than all the other judges together kill of Israel’s foreign enemies.[35] Victor Matthews writes: The ruthlessness of Jephthah’s forces in executing thousands of Ephraimites is perhaps simply an extension of their leader’s determination to win at all costs, a fatal flaw for both him and his people.[36] With this act, Jephthah has finally become governor over all of Gilead.[37] And God’s silence…is deafening. He lets the nation destroy itself. Israel has become its own worst enemy.[38]

7 Jephthah led Israel six years. Then Jephthah the Gileadite died and was buried in one of the cities in Gilead. Judges 12:7

He is buried ‘somewhere’ in Gilead.[39] Scholars are not sure whether this means that there were various memorial services commemorating Jephthah, or whether, based on a Targum commentary[40]…his body was severed into parts and scattered in various burial places![41] The rabbis say that as a punishment for his actions with his daughter, he became diseased, and parts of his body fell away from him and were buried there; hence he was buried in multiple places in Gilead.[42]

Is Jephthah a good guy? He is an illegitimate child, an outcast, who against all odds, makes it to the top—He is a natural leader—but it’s of scoundrels and thugs, and he uses his abilities to gain dominance and distinction. He has good debate skills with foreign leaders—a man of powerful words,[43] but he doesn’t treat his own people well, and it is words that kill.[44] He is all about himself first. He is willing to sacrifice anything and anyone to satisfy his own ambition.[45] He is empowered by the Holy Spirit for the task at hand, but he foolishly bargains with God in a vow that costs him his only daughter. Jephthah could be seen as a faithful person who made the best of his life, OR a cynical politician who uses religion in his quest for political power and position.[46]

But Jephthah IS portrayed positively in other places. He is included in the Hebrews hall of fame, which we read last week. If Scripture only held up those who had no sin, then Hebrews 11 would not have been written. When Samuel, the last judge, and prophet of the people, was making his farewell speech before Saul become king,

Samuel said to the people, “It is the Lord who appointed Moses and Aaron and brought your ancestors up out of Egypt. 7 Now then, stand here, because I am going to confront you with evidence before the Lord as to all the righteous acts performed by the Lord for you and your ancestors. 8 After Jacob entered Egypt, they cried to the Lord for help, and the Lord sent Moses and Aaron, who brought your ancestors out of Egypt and settled them in this place. 9 But they forgot the Lord their God; so he sold them into the hand of Sisera, the commander of the army of Hazor, and into the hands of the Philistines and the king of Moab, who fought against them. 10 They cried out to the Lord and said, ‘We have sinned; we have forsaken the Lord and served the Baals and the Ashtoreths. But now deliver us from the hands of our enemies, and we will serve you.’ 11 Then the Lord sent Jerub-Baal, Barak, Jephthah and Samuel, and he delivered you from the hands of your enemies all around you, so that you lived in safety. 1 Samuel 12:6-11

Jephthah, for all his faults, DID trust in God to bring justice and grant victory for Israel.[47] He proclaims that God is the ultimate judge.[48] His story is a reminder of God’s grace in some of the darkest moments of Israel’s history.[49] When God’s people cry out, God shows mercy, even when their apologies were so pathetic. It reminds us that our focus must be on God as well in these tales of the Judges. Jephthah’s story comes to an end in the book of Judges. The minor judges bookend the tale of Jephthah. We talked about Tola and Jair in chapter 10, and now there are three more.

8 After him, Ibzan of Bethlehem led Israel. 9 He had thirty sons and thirty daughters. He gave his daughters away in marriage to those outside his clan, and for his sons he brought in thirty young women as wives from outside his clan. Ibzan led Israel seven years. 10 Then Ibzan died and was buried in Bethlehem. Judges 12:8-10

Ibzan comes from Bethlehem—probably the most famous southern city in Judah.[50] He has the ideal family of thirty sons, but also thirty daughters.[51] An old Hittite story tells of the Queen of Kanish who gives birth to thirty sons in a single year. Overwhelmed, she places them in baskets and sends them down the river where the gods rescue them and raise them to adulthood. Later she gives birth to thirty daughters, but those she keeps. In time, the sons return ‘driving a donkey’, and without divine intervention and quick thinking, they would have married their own sisters.[52] Ibzan has high ambitions. He marries off his children to make political alliances. It’s good politics, but bad religion.[53] The same kinds of alliances will be made later by King Solomon and Jeroboam, who lose their way in following God.

11 After him, Elon the Zebulunite led Israel ten years. 12 Then Elon died and was buried in Aijalon in the land of Zebulun. Judges 12:11

Elon’s name means oak or terebinth.[54] There are no special accomplishments listed other than he led for ten years!

13 After him, Abdon son of Hillel, from Pirathon, led Israel. 14 He had forty sons and thirty grandsons, who rode on seventy donkeys. He led Israel eight years. 15 Then Abdon son of Hillel died and was buried at Pirathon in Ephraim, in the hill country of the Amalekites. Judges 12:13-15

Abdon’s family situation sounds similar to Jair’s a couple of chapters back. He had a wide area of influence and jurisdiction.[55] Abdon has a royal family of seventy descendants,[56] which you may remember—Gideon did as well.[57] Jephthah only led six years. Ibzan, Elon, and Abdon each led longer, but not as long as Tola and Jair, who came before Jephthah. From the short statements about these final three, it seems they are interested in political alliances and family riches.[58] But there are also times of peace. These three judges have no special qualifications, nor did they rise up in response to any known crisis.[59] It reminds us that we do not have an in-depth account of what happened during this time. There were periods of oppression and periods of prosperity, and deliverers were raised up.[60] We know by now that the peace will not last, and we’re seeing that the nation is rapidly spiraling into chaos. As we look back at the Judges, it’s easy to ask: “Why are there so many unlikely leaders? Will a leader finally come who can bring the nation together? Has God given up on his people?”[61] Through Jephthah, God delivered the people of Israel from Ammonites, but not the Philistines.[62] Our next judge will focus on the deliverance from the Philistines.

The story of Jephthah is filled with conflict. He locks horns with his own family, he contested his position with his own tribe, He stirs up the dispute with the Ammonites and goes into combat, and ramps up the hostility with another Israelite tribe. His whole life has been characterized by contention.[63]

Jephthah chose a culture of conflict

The story of Jephthah ends not with victory over enemies, but with tragedy among brothers. What began as God’s deliverance— turned into Israel’s division. The people of Israel became fragmented with tribal, spiritual, and linguistic division.[64] Before we shake our heads at them, we have to ask: where do we do the same? Where do we draw our own “Shibboleths,” testing who belongs—based on words, preferences, or pride? The Ephraimites and those who lived in the Gilead region were brothers, but pride and pain turned them into enemies. They are so TRIBAL! Literally! It’s the same thing we see all around us today. Today our “tribes” aren’t called Ephraim or Manassah, or Judah: they’re denominations, political identities, and personal preferences. We divide by generation — “Boomers don’t get it,” “Gen Z doesn’t care.” We separate online, where outrage earns applause and humility gets ignored. We belittle others in comment threads, “calling out” fellow believers, or people in opposite political parties publicly instead of seeking private reconciliation. We measure each other by where we live, what we read, how we parent, or how we vote. Even in the church, we draw lines — over theology, worship style, or tradition —as if music or method could measure holiness. Our Unity becomes conditional: “You’re welcome here — as long as you think like me.” Belonging to the same family of faith means little if we don’t live out humility, grace, and peace. Jephthah spoke more words than any other judge[65], and yet his words became his undoing. Our words have the power to destroy us,[66] too. Complaints and criticism divide; encouragement and blessing heal.

Dwight L. Moody once met a critic who said, “I don’t like the way you preach the gospel.” Moody replied, “I’m always willing to learn. Tell me about the method you use.” The man said, “I guess I don’t have one.” “I’ll tell you what,” Moody said, “I like the way I do it better than the way you don’t do it.”[67]

We need to lead with example, encouragement, and edification. Bitterness, left unchecked, devastates both personal and communal life and brings dishonor to the gospel. I heard just this week of a local church torn apart by disagreements —leaders refusing to meet in person, to concede, or to confess, led to fragmentation. It’s all too common. God calls His people to speak and act in ways that build unity rather than division. As followers of Jesus, we must:

Words can build bridges or dig trenches. Pride in our brand of faith can make us forget the One we’re following. Our accents of grace should mark us as Christ’s —not perfect words or polished theology, but with the kind of love that comes from God. So pause and consider: Who have you written off because they don’t fit your circle or your views? Where do you insist on being right instead of being reconciled? What tone do your children hear in your voice — peace or pride? What would humility look like in your friendships, your marriage, your home? If you’ve contributed to conflict — even quietly —what’s one step toward repair? A conversation? A confession? A kindness?

Christ calls us to humility — not to prove who’s right, but to pursue what is good. Jesus said, “Out of the overflow of the heart the mouth speaks.” (Luke 6:45) “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another.” (John 13:35) There are times to set boundaries — and times to recognize when we’ve been part of the problem. Paul writes, “If possible, and to the extent that it depends on you, live at peace with everyone.” (Romans 12:18 CJB) Imagine if we thought before we spoke: “Will this build up or tear down? ‘What if we refused to weaponize words —and practiced peacemaking speech instead: to compliment, to encourage, to apologize, to bless — even when it costs our pride? The Apostle Paul writes to the church: “Make every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace.” “Do not let any unwholesome talk come out of your mouths, but only what is helpful for building others up.” (Ephesians 4:3,29) When we elevate pronunciation, phrasing, or style above grace, we are squabbling over semantics instead of pursuing peace. The gospel calls us to move from Shibboleth to Spirit—from prideful tests of belonging to shared grace in Christ. Mark Boda and Mary Conway write: “The gospel provides hope because it is rooted in a love relationship between God and humanity that opens the way for loving relationships between humans.” [68]

Relationship health begins at home—which is why it is so important to practice the rhythms of loving, forgiving, submitting, and honoring.[69] So, parents—model grace-filled speech. Let your kids hear forgiveness in your home. Students—be the bridge in your friend group. Refuse gossip. Invite the outsider in. Singles and newlyweds—practice humility in how you handle conflict — listen first. Empty-nesters and elders—Use your voice to bless the next generation. Your encouragement is leadership. The tragedy of Judges 12 isn’t just the bloodshed—it’s the waste of energy on the wrong fight. Jephthah’s story ends with brothers in a phonetic fight over a word that revealed not just their dialect, but their hearts. Let’s not repeat that. Let’s be known for Christlike community—for words that heal, homes that forgive, and hearts that choose peace.

PRAYER: Lord, we’ve heard Your Word today — a story of brothers divided, a warning about words that wound, and a call to choose grace over pride. Forgive us, God, for the times we’ve spoken carelessly, for when we’ve built walls instead of bridges, for when we’ve cared more about being right than being reconciled. Teach us to speak with the tone of heaven—words marked by love, patience, and humility. Let our homes echo with forgiveness, our friendships with gentleness, our church with peace. When pride whispers that we must defend our place, remind us that Christ laid His life down for us. When we feel rebuffed or overlooked, remind us that You see us and call us beloved. When conflict rises, make us peacemakers who reflect Your heart. Unite us, Lord —not by preference, but by Your Spirit; not by uniformity, but by Your love. May our words this week bring life, our actions sow peace, and our community reveal Christ to the world. We pray this in the name of the One who reconciles all things, Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Bibliography

- Block, Daniel I. Judges, Ruth, Nashville: B&H Publishing Group, 1999.

- Boda, Mark J., Mary L. Conway, Daniel I. Block, general editor; Judges, Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament, Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, 2022.

- Brown, F; S. Driver, and C. Briggs, The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon, Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2010.

- Butler, Trent C., Word Biblical Commentary: Judges, Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009.

- Frolov, Serge, Judges, Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2013.

- Frymer-Kensy, Tikva, Reading the Women of the Bible: A New Interpretation of their stories, New York: Schocken Books, 2002.

- Inrig, Gary, Hearts of Iron, Feet of Clay, Chicago: Moody Bible Institute, 1979.

- King, Philip J., Lawrence E. Stager, Life in Biblical Israel, Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001.

- Soggin, J. Alberto, Judges, Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1981.

- Smit, Laura A. and Stephen E. Fowl, Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible: Judges and Ruth, Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2018.

- Matthews, Victor H., Judges & Ruth, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- McCann, J. Clinton, Judges, Louisville: John Knox Press, 2002.

- Wilcock, Michael, editor, J.A. Motyer, The Message of Judges: Revised Edition, Downers Grove: Illinois, 1992, 2021.

Articles

- Hendel, Ronald S. “Sibilants and šibbōlet (Judges 12:6)”, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, Feb. 1996, No. 301, 69-75.

- Hoffner, H.A., “A Tale of Two Cities: Kanesh and Zalpa,” Hittite Myths, Writings from the Ancient World 2, ed. G.M. Beckman (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1990), 62-63.

- Landy, Francis, and פרנסיס לנדי. “הסיסמה ‘שיבולת’ / ‘SHIBBOLETH’: THE Hoffner

- PASSWORD.” Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies / דברי הקונגרס העולמי למדעי היהדות י (1989): 91–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23530811.

- Woodhouse, Robert, “The Biblical Shibboleth Story in the Light of Late Egyptian Perceptions of Semitic Sibilants- Reconciling Divergent Views”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 123, No. 2, Apr-Jun 2003, 271-289.

- Zucker, David J., “Jephthah: Faithful Fighter; Faithless Father Ancient and Contemporary Views”, Biblical Theology Bulletin Volume 52 Number 1, 2021, 37–47.

Websites—accessed between October 27-31, 2025

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Winnie-the-Pooh_characters

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sibilant

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/lortv/posts/1212707143197647/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gopher_(Winnie_the_Pooh)

- https://www.hebrew4christians.com/Grammar/Unit_One/Aleph-Bet/Shin/shin.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nl-Schibbolet-fries.oga

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_shibboleths

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/high-vowel

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%A0#:~:text=The%20grapheme%20%C5%A0%2C%20%C5%A1%20(S,voiceless%20retroflex%20fricative%20%2F%CA%82%2F.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5VaCg3NtCE0

—

Going Deeper Questions

The gopher from Winnie the Pooh wasn’t in the original book, but he popped up in the movie — and he is typically remembered by his funny “S” sound. What’s a funny mispronunciation, accent, or word-mix up story you’ve experienced or heard?

-How do accents or differences in speech shape how we see people — and how they see us?

Read Judges 12:1-3 (Pride, Pain and Poor Communication)

–How would you describe the tone of this exchange if it happened today—defensive, sarcastic, wounded, proud?

-Why do you think Ephraim was so offended that Jephthah didn’t call them to battle? What might have been fueling their pride or insecurity?

-How do you personally react when you feel left out or overlooked?

-How did Jephthah’s words escalate the situation instead of calming it? (Compare this to Gideon’s gentler response in Judges 8:1–3).

-Which response do you tend to lean toward—Jephthah’s defensiveness or Gideon’s diplomacy?

-Can you think of a time when someone (maybe you!) overreacted before hearing the whole story? Why do you think we sometimes jump from hurt feelings to drama so fast?

-Do you think Jephthah’s lifelong story of rejection (Judges 11:1-3) may have been a part of his reaction? How have your old wounds ever shaped the way you handle conflict?

-Jephthah says he did call, and Ephraim says he didn’t.

How can miscommunication like this happen in families, churches, or teams?

Read Judges 12:4-6 (Words that Divide)

–The Ephraimites’ insult—“You Gileadites are fugitives”—(vs 4) reduced identity to geography. How do we still reduce people to categories today? (Think: “They’re liberal,” “They’re fundamentalist,” “They’re city people,” etc.)

-When have you been on the receiving end of a label, and how did it affect your desire to belong?

-Jephthah was willing to negotiate with outsiders but fought with his own people. Why is it often easier to show grace to strangers than to family or fellow believers?

-Try saying “Shibboleth” and “Sibboleth” out loud. Practice saying it with a whistling ‘S’ like the gopher in Winnie the Pooh. Who in your group can say it best?

-What’s funny about judging people by pronunciation — and what’s not so funny when we realize we actually do that in life?

-The word Shibboleth meant “stream” or “grain”—something life-giving, but it became a word of death. What are some “modern Shibboleths” — ways we test who belongs, decide who’s really one of us, or judge others by small differences (in speech, education, style of music, theology, social status, or political views)?

-How do you respond when someone “says it wrong”? Have you ever caught yourself squabbling over semantics instead of pursuing peace?

-Why do you think people sometimes feel safer policing language or theology than practicing grace?

Read Judges 12:7-15

–What details stand out to you about how Jephthah’s story ends?

-What do you notice about the descriptions of the three judges who follow him (Ibzan, Elon, Abdon)? What seems to matter most to them?

-None of these judges are said to cry out to God, deliver Israel, or lead repentance. What does that silence reveal about the nation’s spiritual health?

-Which do you think is the greater danger for God’s people today: open conflict or quiet complacency? Why?

-If you were remembered in one or two sentences, what would those sentences say?

-God doesn’t intervene in this chapter. Why do you think the narrator leaves Him silent?

-How do you respond when you sense God’s silence in the middle of conflict—fight harder, withdraw, or seek Him more deeply?

Choose Christlike community over a culture of conflict

Read Ephesians 4:29-32

Do not let any unwholesome talk come out of your mouths, but only what is helpful for building others up according to their needs, that it may benefit those who listen. 30 And do not grieve the Holy Spirit of God, with whom you were sealed for the day of redemption. 31 Get rid of all bitterness, rage and anger, brawling and slander, along with every form of malice. 32 Be kind and compassionate to one another, forgiving each other, just as in Christ God forgave you.

–How are we called to speak differently than Jephthah’s men?

-What does it mean to be a community where people don’t have to sound the same to belong?

-What are some practical ways to create a Christlike community in your context: In your church? In your family? Online?

Application and Practice (Building Bridges instead of Barriers)

–If your “accent” revealed your faith — what would others hear most clearly: pride, criticism, or grace?

-Words can build bridges or dig trenches. What’s one practical way you can build a bridge this week — at home, at work, or in your friend group?

Prayer

Start with a time of Silence: Pray silently for one relationship that needs healing. Then pray this prayer: Lord, teach us to speak with Your accent — words marked by love, patience, and humility. Forgive us for careless words and prideful hearts. Make us peacemakers in our families, our friendships, and our church. Let our words this week bring life, our actions sow peace, and our community reveal Christ to the world. Amen.

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=olOXVskDwOs

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Winnie-the-Pooh_characters

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sibilant

[4] https://www.facebook.com/groups/lortv/posts/1212707143197647/

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5VaCg3NtCE0

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gopher_(Winnie_the_Pooh)

[7] Based on Mark J. Boda, Mary L. Conway, Daniel I. Block, general editor; Judges, Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament, Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, 2022, 560-561.

[8] Victor H. Matthews, Judges & Ruth, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, 129.

[9] Ronald S. Hendel. “Sibilants and šibbōlet (Judges 12:6)”, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, Feb. 1996, No. 301, 69-75, 72.

[10] Judges 10:6

[11] Based on Boda, Conway, 557.

[12] Daniel I. Block, Block, Judges, Ruth, Nashville: B&H Publishing Group, 1999, 385.

[13] Laura A. Smit, Stephen E. Fowl, Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible: Judges and Ruth, Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2018, 141.

[14] Trent C. Butler, Word Biblical Commentary: Judges, Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009, 294.

[15] Block 380.

[16] Gary Inrig, Hearts of Iron, Feet of Clay, Chicago: Moody Bible Institute, 1979, 199.

[17] Judges 8:3a

[18] Based on Boda, Conway, 562, 563.

[19] The NIV uses ‘renegade’, but the NASB’s ‘fugitives’ is preferable—per Block, 383, footnote 153.

[20] Block, 383.

[21] Francis Landy, Hibboleth, 94.

[22] Francis Landy, “SHIBBOLETH”- THE PASSWORD, פרנסיס לנדי Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies, Vol. י, Division A- The Bible And Its World 1989, 91-98, 92.

[23] Daniel I. Block, 384.

[24] Victor Matthews, 129.

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nl-Schibbolet-fries.oga

[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_shibboleths

[27] Ambrose, Stephen E., D-Day. New York: Touchstone, 1994, 191. ISBN 0-684-80137-X.

[28] Robert Woodhouse, “The Biblical Shibboleth Story in the Light of Late Egyptian Perceptions of Semitic Sibilants- Reconciling Divergent Views”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 123, No. 2, Apr.-Jun. 2003, 271-289, 286.

[29] https://www.britannica.com/topic/high-vowel

[30] Hold down the s on the Mac and the symbols will show.

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%A0#:~:text=The%20grapheme%20%C5%A0%2C%20%C5%A1%20(S,voiceless%20retroflex%20fricative%20%2F%CA%82%2F.

[32] Woodhouse, 286.

[33] Ronald S. Hendel, Sibilants and šibbōlet (Judges 12-6), Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 301, Feb. 1996, 69-75, 72.

[34] Francis Landy, Hibboleth, 95. She uses the word ‘sword’, which I avoided because of the tie with the Word as a Sword in Hebrews.

[35] Trent C. Butler, 300.

[36] Quoted by Butler, 296—Matthews, 130?

[37] Boda, Conway, 565.

[38] Block, 384.

[39] Boda, Conway, 567.

[40] Boda, Conway, 567, footnote 3 (referencing The Targum of Judges as translated by Smelik)

[41] Butler, 297.

[42] David J. Zucker, “Jephthah- Faithful Fighter; Faithless Father Ancient and Contemporary Views”, Biblical Theology Bulletin, Feb 2022, 37-47, 43. Genesis Rabbah 60.3; Leviticus Rabbah 37.4; Ecclesiastes Rabbah 10.13,1–15, 1.

[43] Butler, 300.

[44] Butler, 300.

[45] Block, 386/

[46] Butler, 299.

[47] Boda, Conway, 568.

[48] Butler, 300.

[49] Boda, Conway, 574.

[50] Butler, 297.

[51] Block, 389.

[52] Block, 389, footnote 174. For the full story see H.A. Hoffner, “A Tale of Two Cities: Kanesh and Zalpa,” in Hittite Myths, Writings from the Ancient World 2, ed. G.M. Beckman (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1990), 62-63.

[53] Butler, 297.

[54] Block, 389.

[55] Butler, 298, citing Brown.

[56] Block, 390.

[57] Judges 8:30

[58] Butler, 298.

[59] Butler, 299.

[60] Block, 391.

[61] Butler, 297.

[62] Judges 10:7

[63] Block, 381.

[64] Block, 386.

[65] Block, 387.

[66] Boda, Conway, 573.

[67] Inrig, 199, 200.

[68] Boda, Conway, 574.

[69] Boda, Conway, 574.